In the late 1980s, Canadian documentary maker Patrick Watson went around the world, trying to get a handle on “democracy.” He went to many places in the world, some democratic, some not quite so, and interviewed many political leaders, like Robert Mugabe and Momar Gaddafi. In Watson’s Struggle for Democracy, he could not define “democracy.”

I have settled on this quick definition:

After the ballot box speaks, the losing side allows the winning side to govern.

This might seem common knowledge, even to the point that it does not deserve saying. But this yielding to the ballot box has not been a natural feature of humanity’s history. Much more often than not, an unwanted ruler had to be thrown out of his rule with forces much bigger than a ballot box. In other words, western democracy is not natural to humanity.

Or in other words, we had to learn how to move away from our various versions of oligarchy and toward letting a ballot box decide our rulers. We common people had to learn how to use our vote. The overly ambitious people who want to govern us had to consider some of the aspirations of the common people to be allowed to govern. Three hundred years ago, this was a big jump in our thinking of how to structure a society.

Making another big jump

I am the inventor of Tiered Democratic Governance (TDG). Moving from western democracy to the TDG will be about as big of a jump as moving from oligarchy to western democracy. We will learn new ways — again.

“But we are really not a democracy”

When I use the term “western democracy” in my TDG promotions, I often get the above comment. Let’s analyze the truthfulness of this statement.

My heritage is the peasant classes of Eastern Europe. Two hundred years ago, the rulers of those times believed this class was not worthy of an education. So most children born into that class did not get one — and stayed in the peasant class for the rest of their lives. To both the rulers and the ruled, this was an acceptable way to structure society.

Then in 1848, Europe went through a big social upheaval. To keep social order, the aristocratic classes had to grant some concessions to the peasant classes. One of the concessions was primary education of their children. Before being assigned to fields or mines or factories or childcare, my four grandparents were given a Grade 4 education, with basic reading/writing/math, thanks to the 1848 revolutions.

Grade 4 does not sound like much, but this education allowed my ancestors to read a newspaper. They could observe more closely the happenings of their society. Even though my ancestors did not have a vote, their rulers were more responsive to their needs. The rulers remembered 1848.

Several generations later, one of my grandparents’ progeny has written a book about replacing our current democracy with an advanced democracy. Think about that for second! My natural destiny was to be a farm laborer or a miner. There was no education in that boy’s future. Just put him to work at a work worthy of the status of his parents. And here I am: writing about a new democracy!

I credit western democracy as an essential reason for me to develop my ideas, write my books, and participate in this discussion. I could not have done this project without an education. I could not have done this project with only a Grade 4 education. So when I hear a comment “Well, we are not really a democracy anyways,” I can only shake my head. I have had more opportunities and freedoms than my grandparents had when they left Ukraine in 1922 and Slovakia in 1936.

But, Dave, we are not a democracy

There is some truth to this statement.

Here is a short list of flaws of western democracy. Most readers will agree with this list.

Western democracy:

1. too often does not put the better people in public office,

2. gives too much influence to the wealthy,

3. has a mischievous media with political, ideological, or profit motives,

4. teaches us to fight for our ideas, rather than see things from different angles,

5. has far too much corruption, and

6. survives mostly because it is “better than whatever has been tried before.”

Here is my vision of a future democracy. Again many readers will agree these points are more democratic than the above points. An ideal democracy:

1. elects the better people to govern us,

2. give good reason for citizens to respect their political leaders,

3. has a clear due process to make decisions,

4. incorporates the perspectives of various stakeholders,

5. evaluates alternatives — and their pros and cons — in an open and frank discussion,

6. comes to a decision, knowing that some people may still not like that decision,

7. amends that decision when it proves to be not working, and

8. gives citizens confidence the decisions usually work out well.

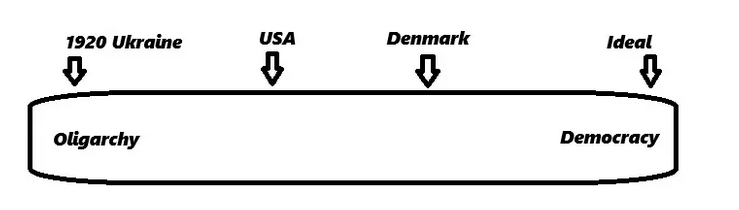

Allow me to plot a linear paradigm. On one extreme, we have the oligarchy my Ukrainian grandparents came from; my grandparents did not have much say in their society. Had they stayed in Ukraine, they would have likely faced the Holodomor genocide. The other extreme is the democracy we all yearn for. Here is the base for my paradigm:

My Slovak grandparents lived in an emerging, struggling democracy. And the Czechoslovak government was making important changes to their new country. So most Slovaks had more opportunities in the 1930 Czechoslovak democracy than the 1910 Hungarian oligarchy that preceded it. Yet my paternal grandparents still emigrated to Canada. Unknowingly, they got away from the onslaught of Nazism, and later communism. I would put 1930 Czechoslovakia one quarter of the way into the paradigm:

Obviously western democracy does not fulfill the requirements of our ideal democracy. But it is also certainly not the oligarchy my Ukrainian grandparents left behind. I would put western democracy half-way between the two extremes.

My paradigm would now look like this:

Political scientists often talk about “getting to Denmark,” which is their way of saying that we should aspire to be more like Denmark. Denmark has a unique blend of capitalism and socialism, with both great social programs and multi-national corporations. Their citizens score highly on various humanitarian indexes, like education, longevity, and happiness.

On the paradigm, I now replace “western democracy” with Denmark and USA. Placements are based on my interpretation of my list of democratic traits.

This paradigm demonstrates is democracy is not some kind of fixed point, either we have it or we do not have it. Rather democracy is a greyscale. Today’s democracies exhibit traits of both our utopic democracy and traits of an oligarchy where only a few people make the decisions for society.

In other words, democracy is a moving target. We can be moving forward. Or we might be moving backward. But nowhere do we find a country that we can call 100% democratic.

Even citizens of Denmark have contempt for their politicians and their decisions. And the right-wing is rising in the Nordic countries.

Democracy and the TDG

As most of my loyal leaders know, I believe my TDG will achieve the utopia we are so looking for.

And when we reach this utopia, we just might be seeing a higher level of democracy that nobody can see today:

Democracy is a greyscale. Rather than argue whether our democracy is or is not a democracy, let’s make whatever we have more democratic. The TDG will take us down this path.

Investigate the TDG — for the sake of your great-grandkids.

For the sake of people around the world who do not have as much opportunity as you to build a new democracy.

Published on Medium 2024

Environmentalists Should Build the TDG

Book Review: Recreating the World